I should probably begin this post with a disclaimer. I’ve never been a fan of ‘Wuthering Heights.’ I first read it as a teenager, looking for another fiction hero to fall in love with and I was, simply, disgusted. As far as I could see, Heathcliff was an abusive puppy-murdering sadist.* I was angry at the novel and I was really really angry that it was being sold to young girls as a model for ideal relationships. I re-read it a bit later, in a slightly more accepting mind frame (this time I knew what to expect) and was willing to concede that it had some powerful gothic scene setting, but I’ve always been highly ambivalent about this most famous Brontë novel.

Before I get attacked for my lack of romance and literary appreciation, I’m going to devote this post to explaining why I have changed my mind. I still hate Heathcliff, but I’ve just finished an extremely enjoyable re-read during which I fell in love, not only with Hareton (my new literary crush) but also with the novel as a whole, which I can finally appreciate as possibly the best-structured of any Victorian novel I’ve encountered.

Firstly, there’s the timing. The book takes place over an extremely precise time period, which frames and gives enduring meaning to the story:

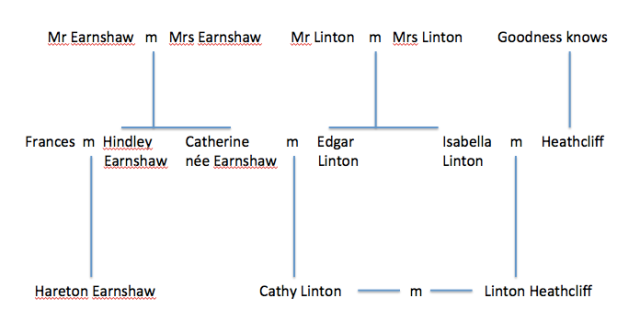

Part 1: It’s November and Mr Lockwood, a young man rather in love with the idea of living in splendid moody isolation away from the world goes to visit his new landlord, Heathcliff, at Wuthering Heights. He meets all the remnants of the Earnshaw/Linton/Heathcliff family (see family tree below) and has an introduction into their frightening past and gloomy present. The snow is thick on the ground as he leaves Wuthering Heights; it’s the start of a long winter.

Part 2: From November to January, Mr Lockwood is ill from his night at Wuthering Heights. Nelly Dean tells him the story of the inhabitants, from Heathcliff’s introduction to the Earnshaw family right up till the current winter.

Part 3: It’s January, the worst of winter is over and Lockwood has recovered. He goes back to visit Wuthering Heights, partly to explain to Heathcliff that he will be moving to London, probably until his lease is up.

Part 4: It’s late summer (September). Lockwood revisits the neighbourhood and Nelly Dean brings him up to date with what has happened to the inhabitants of Wuthering Heights.

As you can see, the book has two timelines, one of which follows the natural year, from the chill death of winter through spring and up till a late and abundant harvest. Simultaneously, we have a story that goes back in time and that always works towards a clear end-point bringing Lockwood and the reader up to date, given they’ve already seen a snapshot of the results of these actions.

The beautiful simplicity of the structure outlined above would be enough for the novel stand out as exceptional, but there’s more. On re-reading I was finally able to see how every significant relationship in the book is an exploration of love, especially obsessive, romantic love. Using the family tree, I’m going to be making the case for the novel providing a pretty comprehensive picture of varieties of love and saying how the conclusions are possibly more moral and less tempestuous than you might expect.

Motherly love: the oldest generations of mothers in the family are pretty insignificant. Two of the next generations of mothers die in childbirth; the third survives, but she leaves the pages of the story at this point so we never actually see her relationship with her son. The most maternal figure in the novel is Nelly Dean, and she’s hardly a beacon of maternal affection. Though she raises and claims to adore Hareton, she later disowns him for his uncouth behaviour after they are separated. Similarly, she loves young Cathy, but not unconditionally, certainly not uncritically.

Fatherly love: Fathers in this book are either abusive and/or neglectful or are doting and disappointed. They tend to die at moments that cause maximum trauma to their guilty offspring.

Obsessive love: there’s just so much of it in the novel, I’m going to have to use more subheadings:

Hindley Earnshaw loves Frances with a destructive passion. No one else thinks much of her and the general consensus appears to be that she isn’t worth it, but we’re told: He had room in his heart only for two idols – his wife and himself: he doted on both, and adored one.‘ Frances’s death leads directly to a gambling and alcohol addition which will destroy Hindley’s life and fortune. The general moral appears to be that selfish obsessive love is a bad thing and that weak characters especially should really try to avoid it.

Edgar Linton loves Catherine blindly and passionately. I know that neither Nelly nor Catherine nor Heathcliff really give him much credit for his unrequited passion, but it’s very hard to interpret his actions in any other way. Certainly he loves her above anything else, including God – his final wish is to be buried next to her, out on the moors, rather than in the consecrated churchyard.

Isabella Linton, poor Isabella Linton loves Heathcliff. She elopes with him and puts herself completely in his power, all for love. It gets confusing because of the different voices telling her story, but we do know that her husband takes joy in tormenting her and one time she tells Nelly that she hates him for this treatment his response is truly chilling. ‘If you are called upon in a court of law, you’ll remember her language, Nelly! And take a good look at her countenance; she’s near the point which would suit me. No; you’re not fit to be your own guardian, Isabella, now; and I, being your legal protector must retain you in my custody.’ Think of Bertha Mason in ‘Jane Eyre’ and of Helen Graham in ‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.’ Isabella is tragic, powerless and abused wife; her infatuation has done her only harm. Sadly, ‘Wuthering Heights’ as a novel has little sympathy for her, it really doesn’t have any time for unrequited love (see Edgar Linton above).

Catherine and Heathcliff – we all know this one. They love each other, they are each other, they make each other (and everyone around them) desperately unhappy. I will note however that their love is not only mutually destructive it is also of comparatively short duration. Going by one time frame of the novel, it’s over within a year and leaves no legacy as Heathcliff has no living child and Catherine’s daughter subverts her mother’s destiny.

And then, my favourite bit. I have decided on this reading that ‘Wuthering Heights’ is actually a well disguised didactic Victorian novel with a clear moral message – as shown by the fates and characters of the youngest generation.

Linton Heathcliff – Young Cathy’s husband loves only himself and his pitiful, degraded attempts at affection suffer greatly from comparison with the powerful passions that surround him. He’s a typically degenerate Victorian literary creation in which the worst of inheritance and environment combine in a truly unsympathetic character. It comes as no surprise to learn that purely selfish love will never survive the tempestuous claustrophobia of Wuthering Heights. Readers take note, humans need to love each other if they are to avoid Linton’s terrible fate.

Cathy Linton – Young Cathy is not selfish and it seems that the biggest mistake of her life comes from her kind-hearted regard for others rather than herself. Cathy actually takes a very conventional route for the adventurous yet obedient heroine of any traditional gothic romance. Unlike them however, she learns from her actions, and develops through her misfortunes. I must confess I grew to love Cathy on this reading, and I was much assisted in this by paying attention to the timings of the novel (rather than what Nelly says). Cathy appears to spend very nearly one year in numb grief after her father’s death, and her emergence from mourning is handled beautifully. One more thing – Cathy is one of the only characters in the book to genuinely go against her own wishes in order to avoid causing pain to a loved one. Her mother and Heathcliff may boast a lot of passion, but it is young Cathy who really gives us a view of unselfish love in the book.

Hareton – I’ve already confessed to my crush on Hareton, so I may not be completely objective here. Hareton is my kind of Byronic hero, an uncouth diamond in the rough who is rebellious and proud but also capable of profound loyalty and many hidden kindnesses. Hareton is a clear parallel to Heathcliff, effectively abandoned by his father and continually put down by all around him. His role in the book is to show that tempestuous and negative emotions, inherited or encouraged by environment and education, can be conquered. Also, unlike Mr Lockwood, our want-t0-be romantic narrator, Hareton is interested in inner worth as much as a pretty face. Hareton is the ultimate bad boy made good and he’s also not a wife abuser. Readers wanting romance need look no further.

There we are, Wuthering Heights tells a dramatic, action packed story confined by space to the moors and by time to one calendar year. There is a clear trajectory that takes us from the hell of the first visit to the house to a potential vision of Eden at the end. Wonderfully, despite all of the famous demonic overtones, I am also now convinced that Emily Brontë was on the side of the angels. It’s official, I’m a late but very enthusiastic member of the ‘Wuthering Heights’ fan club and I’m so pleased to have finally arrived.

For much more in depth analysis and love of this novel, I recommend www.wuthering-heights.co.uk

___________________________________

* Heathcliff is not actually a puppy murderer, but he only gets off on a technicality. One, I misread the book originally, and it is a dog, not a puppy that he hangs. Two, Nelly finds the dog and saves it. On the other hand, I’m sure he would have acted exactly the same if Isobella’s favourite dog had been a puppy and he never learns of Nelly’s later actions so I still consider him guilty.

You’ve given me food for thought. I read Wuthering Heights as a pre-teen and like you, really didn’t like it. I’ve never particularly been tempted to a re-read as my memory was of abusiveness masquerading as romance. But now I’m thinking I might give it another chance…

As you can see, I was completely won over on this attempt – it really did help to mentally cast out the WH hype and mythology; like you, I couldn’t get on with the conventional reading at all!

Wonderful post, Shoshi! I’ve always loved the dramatic landscape and claustrophobia of the novel but have been puzzled by the violence and irredeemability of the supposed hero of the tale. Reading your post was like a lightbulb switching on – only my British reserve restrained me from leaping in the air and shouting ‘hoorah’!

Forget British reserve – go for ‘Wuthering Heights’ extravagant emotion!

Seriously, I’ve had the same issues as you in the past; finding my way through them has probably earned WH the title of top re-read of the year and meant the whole way through I was having my own ‘hoorah!’ moments.

Good analysis of a dimension in the book we dont see articulated in such detail. Was this book really ever promoted as depicting an ideal relationship? It was our syllabus book when I was 17 and that was never on our minds. We all saw Heathcliff as a tyrant. This is a well structured novel in many ways (the narrator within a narrator) but also has some flaws – mainly that it relies so much on Nelly listening at does to tell us what happened.

By the way I think your spell check has failed yiu – I think the characters name is Isabella not Isobella

I’m jealous of your reading experience – I can’t remember where I learned that Heathcliff was a romantic hero but it was definitely enough to ruin my first reading of WH. So pleased to have got over this now, in fact, I was so in love with it this time, I even relished Nelly’s narrative whereby we hear of unsympathetic self-absorbed people through another unsympathetic self-absorbed narrator. I especially liked the way she disliked all the characters that I disliked and yet without me ever wanting to identify with her – quite a feat of characterisation!

Also, thank you for pointing out the typing error (now corrected), it wasn’t the computer, it was me, possible a testament to my own tempestuous and unchecked response to the book (I’d like to think…)

Super review! Loved the family tree! Bronte

Thank you – I personally think all editions of the novel should contain a family tree because Nelly’s summary of how people are related is just so confusing!

Great details – Now I’m going to have to re-read Wuthering Heights! It has been many years – I think I must have been in my early 20s when I read it.

Sounds like it’s due for a re-read! I look forward to hearing what you think of it this time round 🙂

Fabulous review Shoshi – indeed, ‘redemption’ comes where we see the younger generation overcome themselves. And Cathy Linton of course was given a loving foundation by Edgar

I know – the idea of education (and education leading to redemption) is such an important one in the book, proving it really isn’t all about passionate emotions after all!

I read WH 29 years ago, and though I don’t remember much of the plot, the atmosphere, the violence and the passion are stuck in my memory for ever. I bought a new copy last year in my favourite edition ( Norton Critical Editions which offer fascinating critical material). Here are a few of the essays included in this volume : “Repetition and the Uncanny”, “WH: the Romantic Ascent”, “Sympathy for the Devil : the problem of Heathcliff in film versions of WH”…, plus poems by Emily, and a text written by Charlotte of which I can’t resist giving you an excerpt : “My sister Emily loved the moors. Flowers brighter than the rose bloomed in the blackest of the heath for her; out of a sullen hollow in a livid hillside her mind could make an Eden”. Love it.

Norton Critical Editions are the best! I also own their ‘Wuthering Heights’; it’s on the shelf next to their ‘Jane Eyre.’ For everyday reading I prefer less weighty tomes (while the pages are thin NCEs are never light), you’ve reminded me to go back and re-read the essays though – I think I’ll have much more patience with them now that I also love the novel!

Fantastic analysis. Wow.

Thank you – it really is a fantastic book and I was just so excited to be able to understand some of its genius.

Pingback: The Best of 2016! | Shoshi's Book Blog